In China’s Du’an Yao Autonomous County, villagers have a saying: “Ten per cent land, the other ninety rocks.” I’m travelling through the “three goats area” – its name describes the flinty creatures, the rugged territory and, in particular, the stubbornness of its people – with Li Wei, a minister in the Du’an government, and Stella Kan, a past president of the Rotary Club of Macau who has made this trip in southern China many times in the last decade. We’re on our way to Yong Ping Primary School, situated an hour and a half from Du’an County Town, at the end of a rutted red-dirt road. Led by the Macau club, Rotarians have adopted and rebuilt eight schools in this county of 676,000. Some of- the graduates attend China’s best universities.

Education is a challenge, says Li, who serves as a liaison between foreign nongovernmental organizations and the Communist Party. In China, nine years of basic education is compulsory. Although it is free, many children from farming families are often kept at home to help in the fields or to care for younger siblings. The families who do send their children to school struggle to pay for room, board, and supplies. Most farmers in the area have an annual income of about US$100.

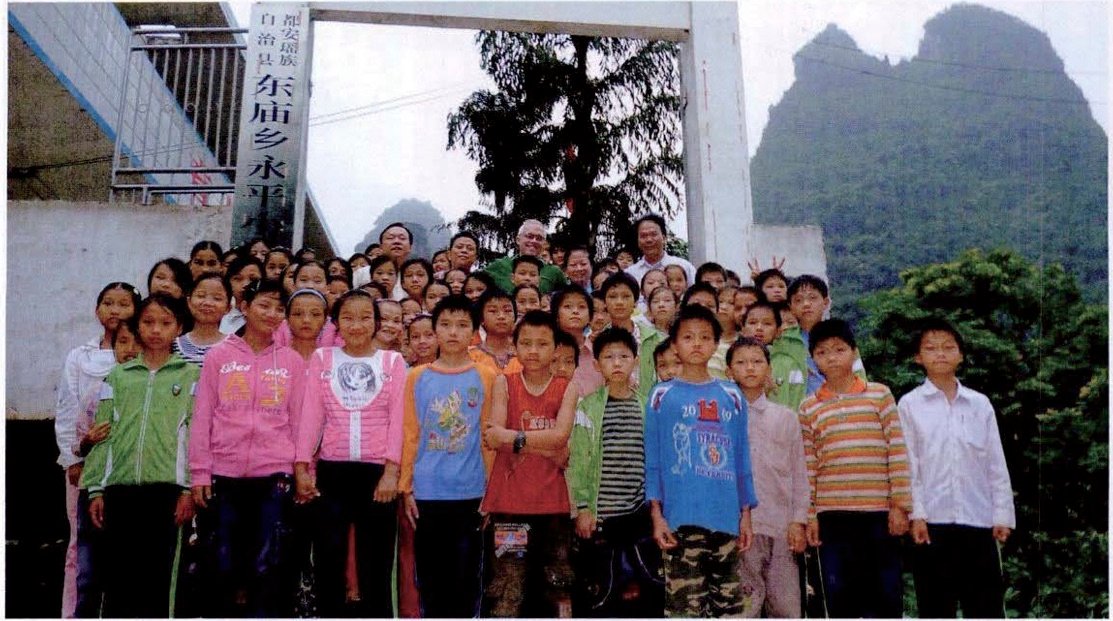

As we arrive at Yong Ping, headmaster Wei Meng Liu and several teachers greet us, and curious schoolchildren surround us. He leads us on a tour of the modest but tidy facilities.

Before the rebuilding of Yong Ping (originally constructed as a Tao temple), he says, “I would be very afraid when it rained.” Teachers dared not touch light switches for fear of electrocution. The new structure safely accommodates 217 pupils, 105 of whom live on-site during the week. “The village is a very humble place,” notes the headmaster, adding that the area is largely undeveloped.

Third grader Wei Li Na says her home got electricity only last year. “Before, we had to use oil lamps for lighting.” A classmate, Lin Jin Bi, beams as she talks about the school, noting that her cousins are envious. “They see that I like the school and that I’m doing well.”

After lunch, we leave for the new, six-classroom Long Yan Primary School, which replaced a structure in danger of collapse, with disintegrating bricks, wobbly pillars, and leaky corrugated steel roofs. It was a 1999 visit here that led Sai Hong Choi, another past president of the Macau club, to come up with a plan to assist the schools.

You could not imagine it then, he says. “When I saw the school, I almost cried. The school teachers were using tree stumps as chairs.” He visited other crumbling schools as well and, back in Macau, appealed to Rotarians in District 3450, which covers Hong Kong, Macau, and Mongolia. The district and its clubs have funded hundreds of schools in mainland China, along with health initiatives such as hepatitis inoculations, and its members are legendary donors to The Rotary Foundation. The Rotary Club of Kowloon North, Hong Kong, joined with the Macau Rotarians. Then the Rotary clubs of Ama, Japan, and Taipei North, Taiwan, signed on. The project also received a total of $5,000 in District Simplified Grants in 2008 and 2009.

A donation from Bill Benter, a past president of the Kowloon North club, was used to restart construction of Du’an Ethnic Experimental Middle School, which for years had mouldered as a four-story shell beside a brackish pond because government funding had stalled. The campus, completed in 2005, now houses science and technology laboratories, a multimedia room so well equipped that it’s often booked for government and business functions, and a dormitory bearing Benter’s name.

“If we had to depend on the county’s investment, we would have had to wait another 10 years to get to this level,” says headmaster Lan Zhi Biao. “Because of Rotary, we have this school. For this, the students look up to Rotary.”

It’s all “embarrassingly good,” according to David Shelton Smith, past president of the Macau club. Communist Party cadres have taken notice of the school’s stellar test scores, and Lan’s summer days are occupied with officials lobbying to have their children placed there. (The headmaster says the admissions process is fair to all applicants.)

The eighth and final school was completed in 2008. The Macau club continues to provide scholarships, furnishings, and supplies to the schools as well as to other needy schools in the area.

“The county town has been transformed into a thriving regional hub city,’ says Benter. “It’s what a philanthropist hopes for – prosperity. The idea of backing education is that students will come out able to thrive. The surprising thing is that it happened far faster than any. body envisioned.”

The changes are easy to see. “When we first came there in 2000, we were interacting with the kids as a visiting delegation,” says Benter. “Middle school kids were asking to take pictures with our digital cameras. When we came back 10 years later, they were taking pictures of us with their cell phones and emailing them back to us.”

– BRAD WEBBER

Clockwise from top left:

At Yong Ping Primary School, the writer (in green) stands beside Stella Kan, of the Rotary Club of Macau.

Girls sit outside their dormitory at Long Yan Primary School. Kan and local government official Wei Wun De visited Du’an Ethnic Experimental Middle School.

Students play table tennis in the courtyard of Yong Ping.

Extract from:

JUNE 2011 THE ROTARIAN

Macau Rotarians led school project in China’s rural mountains